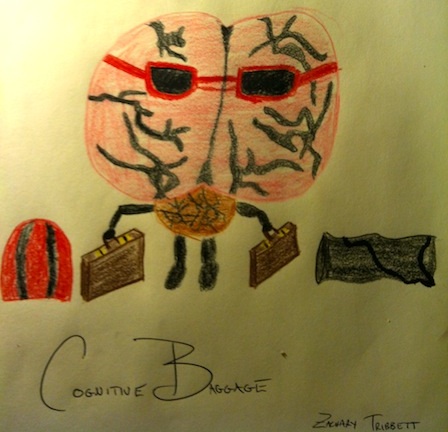

Too Much Stuff: Cognitive Baggage

Stuff. We all have it. Sometimes we want more stuff. Other times we want to get rid of stuff. But in both cases our minds - our brains - are focusing on things, items, property; in a word, stuff. I don’t want to go as far as to say that we are slaves to our stuff; that wouldn’t be prudent. But I do think that all the stuff, all the things that we’ve either owned or experienced does require a non-trivial amount of cognitive capacity, or brain space; something I like to call Cognitive Baggage.

Try and think back to an ex-girlfriend or ex-boyfriend. Remember when you broke up? I’m sure it sucked. Part of the reason why it sucked was because of the emotional baggage your brain took with it at the end of the relationship. During the relationship your brain built emotional dependencies based on various “dating” stimuli, like getting ice-cream, watching movies, or late-night phone calls. When the dating ended, your brain had to transfer those dependencies - that baggage - from your emotional brain (i.e. feelings) into your mental brain (i.e. memory). As I’m sure you remember, it’s a lot of work to get over an Ex; a lot of work to get rid of that emotional baggage.

I think Cognitive Baggage works in a similar way, where the baggage is defined as the dependencies you have built based on your relationship with things, with stuff.

Let’s investigate the relationship with a few common items: keys, phone, and wallet. At any given point my brain is trained to subconsciously be aware of the location of my keys, phone, and wallet. Left pocket, right pocket, back pocket. On dresser, on desk, on desk. These items are my necessities. I must always know where they are because they are what I believe I need - at an absolute minimum - to function. When I forget where I put one of those items, I have a small panic attack; I feel I have lost a part of me: Zach. And that’s what our stuff is: extensions of ourselves.

When we move or think or feel our brain is doing something. It’s changing this to that or moving something from here to there. At least two things happen: we use brain memory and we use brain processing. So when we acquire a new item - more stuff - our brain creates a memory of that item (what it is, where it is, etc.) and also processes that memory (creates associations, categorizes, etc.). Imagine your brain is a computer and you have just written a paper on that computer - a new file or item - more stuff. You save the file by putting it on your hard drive, thereby taking up available computer memory. When you make edits to the file, email it, move it, etc. the computer must do some kind of processing on that file. The more files on the computer, the less space it has and the more processing power required. Just like a computer, as we acquire more stuff our brains must dedicate more memory and cognitive processing power to the cause.

That’s why I try to keep a firm anti-stuff stance. The more stuff I have, the more stuff I have to keep track of and the more brain power it costs me. I would rather save that brain power for thinking about waves or watching Dr. Who. I’m definitely not a minimalist, but I do deliberately consider if an item could truly be an extension of myself and represent my essence before I acquire it. Mo’ stuff, Mo’ problems.

So consider something before you buy it. You don’t have to ask “Do I really need this?” because the answer is most likely, “No.” You should try and ask yourself “Do I really want this?” because the answer, “Yes,” isn’t as frequent as you’d think…

In a much funnier and more eloquent way, comedian George Carlin hits the nail on the head in commenting on society’s obsession with stuff…